Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) is a top-down method for understanding how — and why — systems fail. Start with a single event you want to avoid (the top event) and work backward to map every possible cause. The result is a visual diagram using logic connections that helps teams see complex failure paths, evaluate risk, and improve system reliability.

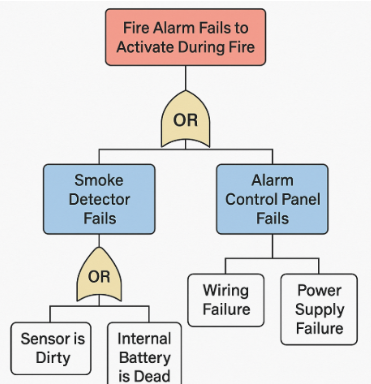

Originally developed in aerospace, FTA is now common in automotive, medical devices, and industrial automation — especially where standards such as IEC 61508 and ISO 26262 make risk management mandatory. An example of an FTA structure is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Simple FTA Structure

Step 1: Identify the FTA objective

Begin by asking why you’re doing the FTA — the objective usually ties to a safety goal or a concern about system failure.

Ask: What am I trying to prevent?

Examples:

Prevent unintended airbag deployment

Prevent a truck from falling into the river at a drawbridge

Your objective will drive the rest of the analysis.

Step 2: Define the top event

The top event is the specific failure you’re studying. Place it at the top of the tree; everything beneath explains how it could occur.

Key rules:

Be specific and focus on an actual failure.

Only one top event per tree.

If you have multiple concerns, create separate trees.

Examples:

Braking system does not activate

Loss of vehicle control

Pump does not deliver fluid

Step 3: Define the FTA scope

Clearly state what’s included and excluded.

Consider:

Which version of the system are you reviewing?

Are you including hardware only, or software too?

Are you examining normal operation, maintenance, or both?

Write the scope down so everyone understands the limits of the analysis.

Step 4: Choose the level of detail

Decide how deep to go.

High-level: systems or functions

Detailed: parts or specific failure modes

Tip: Keep the level of detail consistent across the tree — if you go deep in one area, do the same elsewhere.

Step 5: Set up the FTA ground rules

Before building the tree, agree on organization and labeling.

Use a simple, consistent naming system for events and logic gates.

Decide how to handle repeated events or items you won’t break down further.

Use clear terms so the team shares a common understanding.

Consistent ground rules make the tree easier to read and review.

Step 6: Build the fault tree

Start at the top event and break it down using logic gates.

Common logic gates:

AND gate: all inputs must happen for the result (e.g., loss of communication and sensor failure → system failure)

OR gate: any one input is enough (e.g., power supply failure or processor crash → shutdown)

XOR gate: only one input can occur, not both

Priority AND: events must occur in a specific order

Inhibit gate: output happens only if a condition is true (e.g., weather factor)

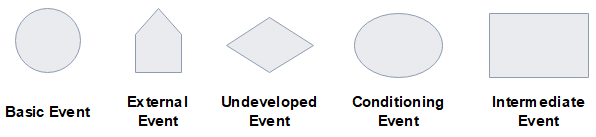

Figure 2: Logic Gates

Types of events:

Basic event: a clear cause that is not broken down further

External event: an event that is normal and guaranteed to occur

Undeveloped event: known but not analyzed further

Conditioning event: a condition that must be true for another event to occur

Build the tree step by step, from top to bottom. Finish each gate before adding more detail.

Figure 3: Event Types

Step 7: Review and evaluate the fault tree

Qualitative review:

Look for combinations of events that could produce the top event.

Check for common-cause failures and weak points.

Quantitative review:

Assign probabilities to basic events.

Use logic to calculate the top event probability — useful for demonstrating compliance with safety targets.

Step 8: Share the results

Turn the analysis into clear, actionable takeaways:

Highlight the most serious failure paths.

Suggest mitigations such as backup systems or additional testing.

Show how the analysis supports or challenges the current safety plan.

This is the part leadership and the rest of the team will care about most — make it easy to understand.

Final tips

Keep logic simple — most trees need only AND and OR gates.

Don’t skip steps — build from top to bottom.

Include human error and external conditions where relevant.

Write each event as a failure, not a state.

Use notes to explain anything complex.